Emotional fight over copper mine at Oak Flat inspires unusual support

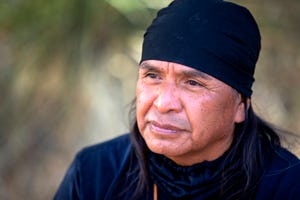

Mario Tsosie and more than two dozen other motorcycle riders rumbled into Oak Flat Campground last month with a mission and a message.

“We had riders come from San Diego, Fresno, Orange County and Los Angeles,” said Tsosie, a Navajo who rides with Redrum Motorcycle Club, the world’s largest Indigenous-based biker group. “It was pretty exciting.”

Tsosie, a member of the Valley of the Sun Chapter of the club, said the Feb. 21 caravan to Oak Flat, about 70 miles east of Phoenix, was almost a last-minute affair. The club had just two weeks to plan the 41-mile ride from San Carlos, capital of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, to the campground. “We’ve been looking for the right time to do this,” he said.

Wendsler Nosie, head of the grassroots group Apache Stronghold, has been living at the campground since November 2019 to focus opposition on a plan by Resolution Copper to build a huge copper mine beneath the site, land considered sacred by many Apaches and other tribes in Arizona.

He seemed surprised when a few dozen motorcycles arrived, said Tsosie. But once the club members explained that they were there to offer support and prayer, the meeting went well.

“It became pretty emotional,” said Tsosie.

Bikers decked out in club colors, jackets and bandannas retrieved hand drums from their saddlebags and delivered an honor song. Nosie discussed why he had relocated to his ancestral home in Oak Flat.

Redrum’s president and founder, Cliff Mateus, had traveled from New York to join the local chapters and out-of-state club members on the ride. Pronounced “Red Drum,” the club engages in supportive activities like raising funds for pandemic relief and medical needs and honors a Native-based code of ethics, said Mateus, who is Quechua and Taino.

“We have a commitment on a spiritual level to stand up for Earth and sacred sites,” Mateus said.

“We stand with those who say ‘enough is enough.'”

Watch video: Redrum Motorcycle Club & Society visits Oak Flat

Tsosie and his fellow riders are part of a group of disparate people and organizations to come out in support of Apache Stronghold, Nosie and several Southwestern tribes as they fight to prevent the handover of Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, also known as Oak Flat, to a British-Australian mining firm.

A law firm specializing in religious liberty cases, a Native blues rock band, a Catholic university law school, students from a Jesuit-run high school in Phoenix, and members of Congress have joined longtime opponents of the mine such as Repairers of the Breach, the Poor People’s Campaign, tribes and environmental groups,even as the clock has been at least temporarily stopped on the land exchange needed for Resolution to start work.

Even a federal agency that works on historic site preservation issues has pulled out of the environmental study process, saying the plan as published will not prevent the site from becoming a giant sinkhole.

For now, opponents will watch what the federal government does next. The U.S. Forest Service rescinded the final environmental impact statement March 1 after a directive from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The land exchange process will be delayed several months as the forest service consults with tribes and other interested parties.

‘The law has done a poor job with Native Americans’

The deal to swap about 2,400 acres of Tonto National Forest land for 5,376 acres of private land to Resolution Copper was made with a last-minute amendment attached to a must-pass national defense spending bill in December 2014 by the late Sen. John McCain and both Republican and Democratic congressmen.

The final environmental impact statement was published by the U.S. Forest Service Jan. 15, which started a 60-day period during which the land swap must be finalized. That period is now on hold after the Forest Service withdrew its decision on the project.

The copper, which lies 7,000 feet below ground level, would be mined using a method known as block cave mining, or panel caving, which would leave a giant sinkhole where Oak Flat now stands.

Resolution, a subsidiary of British-Australian firms Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton (now known as BHP), has said the mine would bring thousands of jobs to the area. The company also said that it has created programs to preserve the threatened Emery oak, an important food source for Apaches and other Native peoples in the area, and would allow access to Oak Flat as long as possible before the ground starts to subside.

Still, the environmental impact statement published by the Forest Service acknowledges that the site will eventually be destroyed as it collapses on itself.

After Apache Stronghold filed a lawsuit to stop the deal, the federal government agreed to wait until at least March 11 to make any move to hand the land over to Resolution. A federal judge turned Apache Stronghold’s request down Feb. 12.

Enter the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a legal and educational institute that defends religious liberty for all faiths, according to its website.

“We’ve been aware of this situation for several years,” said Luke Goodrich, vice president and senior counsel at Becket. “We’re just honored to come alongside Wendsler and Apache Stronghold and all the other members and join in this very important case.”

The Washington, D.C.-based firm has litigated several high-profile lawsuits involving the free exercise of religion, including a case that extended the legal use of eagle feathers to state-recognized tribes and defending sacred sites.

Becket is also well-known for defending craft store chain Hobby Lobby’s policy to deny certain forms of birth control to female employees because the privately-owned corporation felt it was tantamount to abortion, which the owner’s religious beliefs forbid.

After Apache Stronghold’s request for an emergency injunction to stop the swap was turned down by the U.S. District Court, Becket stepped in and filed an appeal with the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Feb. 23.

The government responded to the appeal on March 1, asserting that because the Forest Service halted the land swap process to consult further with tribes, the court no longer needed to issue an emergency injunction because Oak Flat was not in any imminent danger of being lost to the Apache peoples who worship there.

On Friday, the appeals court agreed with the government and said that issuing a preliminary injunction to halt the process on an emergency basis would be “premature.”

The judges expressed no view on the case’s merits and said it would proceed on the court’s originally published schedule.

Goodrich said he feels his client has a substantive case.

“If the government put a fence around Oak Flat and fined Wendsler for trespassing to engage in religious practices, the district court would say there is a substantial burden on religious exercise,” said Goodrich. “But ironically, if the government blasts Oak Flat to smithereens and all that’s left is a crater, and then says that’s not a substantial burden on his religious exercise, that’s simply absurd.”

Native blues rock band: ‘Our song is helping Wendsler’

Robin Hairston was moved to help support a fellow Chiricahua Apache in his quest to prevent Oak Flat from being demolished by a copper mine by doing what he does best: sing.

Hairston, singer and harmonica player for the blues rock band Blue Mountain Tribe, wrote a song to bring attention to the Oak Flat fight as well as other environmental issues facing Indigenous peoples. Hairston said he was also asked by Arvol Looking Horse, a Lakota spiritual leader and keeper of the White Buffalo Calf Pipe, one of the Lakota peoples’ most sacred items, to write songs about preserving the earth.

The band, which has won two Native American Music awards for its hard-driving tunes, went to work and wrote the song “Pray for Our Planet.” The band lacked the resources to produce a video, so Hairston said he called on director, cinematographer and songwriter Michael Altman to help; Altman’s brother Robert Reed Altman shot the video.

Hairston said he has received many emails and messages asking about the Oak Flat issue after the video hit the internet. “Our song is helping Wendsler,” he said.

Hairston said he hopes to travel to Oak Flat soon to meet with Nosie, who hails from the Bedonkohe band of Chiricahua Apache.

‘What it means to be human’

The Apache Stronghold issue was of special interest to Stephanie Barclay, a First Amendment scholar who heads the Religious Liberty Initiative Clinic at Notre Dame Law School.

Barclay and Brigham Young University law professor Michalyn Steele, a Seneca Nation member, recently co-authored a Harvard Law Review article that said Indigenous people should have an easier path to establishing a substantial burden to their religious practices under the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act to resolve inequalities in the law.

Notre Dame is committed to defending religious liberty for people of all faiths, said Barclay, who with her students has already defended Muslim and Jewish people.

She visited Oak Flat and learned about the issue. Barclay said she could see that Oak Flat mattered to Native peoples and that there were consequences if the land lost protection.

“We just believe that it’s part of what it means to be human and human dignity, to be able to pursue and have the freedom to choose whether one is going to practice a faith and whatever that looks like or no faith at all.”

The clinic filed a brief in support of Apache Stronghold’s lawsuit on Feb. 11.

Barclay, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, said somebody posted a tweet about her: “Someone said I was a Mormon director in a Catholic institution representing Muslim voices, defending the Orthodox Jewish community. God bless America.”

Historic preservation council raises concerns

The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation announced on Feb. 11 that it was pulling out of the consultation process on the Oak Flat environmental impact statement process.

It’s the first time in more than 20 years that the council has taken such an action, said Reid Nelson, director of the council’s Office of Federal Agency Programs.

The council advises the president and Congress on national historic preservation policy. It also oversees an important federal environmental review known as Section 106 review, part of the National Historic Preservation Act that ensures the federal government considers effects to historic properties while developing projects such as the Oak Flat environmental impact study.

In the vast majority of the thousands of projects the council is involved in, Nelson said, the agency signs off on an agreement that lays out any effects of the project and any steps the agency, the applicant and others will take to resolve those effects.

“Only about once every year and a half, one of those reviews doesn’t result in an agreement,” said Nelson. Those reviews are usually terminated by other federal agencies for a variety of reasons, he said. Once, the review was terminated by a tribe.

Nelson said the council determined that the measures proposed by the Forest Service would not mitigate or prevent the adverse effects to Oak Flat or the hundreds of other historic properties on the Forest Service land.

“We no longer believed that further consultation would be productive,” said Nelson, who was named acting executive director of the agency on March 5. Instead, the agency will send its comments about Oak Flat directly to the Secretary of Agriculture for review.

Students, lawmakers join the fray

For the first time, students from Brophy Preparatory, a Jesuit-run middle and high school in Phoenix, participated in the Oak Flat Prayer Run to support Apache Stronghold and other opponents of the copper mine project.

This year’s run differed from past years, said Cooper Davis, sustainability coordinator at the school. Usually, the runners converge at San Carlos and run the 41 miles to Oak Flat in a group.But pandemic protocols resulted in smaller groups from different communities converging at Oak Flat on Feb. 27.

“We ran from the north,” said Davis. “We had runners from the Navajo, Hopi and Coeur d’Alene tribes,” he said.

Another student runner claims heritage in the Inupiaq, San Carlos Apache, Navajo and Hopi tribes. Members of the Catholic community joined the 180-mile run from Flagstaff as well, he said.

“When it comes to issues of religious freedom, the Catholic voice should be included in the fight,” said Davis. “The social justice movement has always been part of the Jesuit philosophy, but the willingness to engage in social justice issues has increased throughout the church.”

In late February, 22 members of Congress, including several ranking Democratic members of the House Natural Resources Committee, sent a letter to the then-acting Secretary of Agriculture asking for the Forest Service to withdraw the final environmental impact statement pending review by the Biden administration.

The letter said that the copper mine project would “destroy Oak Flat, use massive amounts of water, harm local ground and surface waters, negatively impact imperiled species, and create a crater up to 1,000 feet deep and roughly 1.8 miles across.

“This is unacceptable.”

The letter may have been part of what the Forest Service called “significant input” during the mandated comment period after its Jan. 15 release of the final environmental impact statemen

t.

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., is preparing a new bill to repeal the land swap, and a congressional spokesperson said that bill is expected to be filed sometime in the next few weeks.

Longtime opponents speak out

Religious leaders from across the U.S. continue to express opposition to the land swap. During a press conference on Jan. 18, Martin Luther King Day, the Rev. Dr. William Barber, who heads the nondenominational group Repairers of the Breach, compared the copper mine project to the destruction of sites that hundreds of millions hold sacred.

“There’s not one group of faith people that would stand by and not stand against this attempt,” said Barber. “We, as people of faith have to stand against that and stand with them. The Apache people have a right to the practice of their religion. It is first guaranteed by God, and it is also a promise in our Constitution.”

The Rev. Robin Tanner of the Unitarian Universalist church spoke out against the land swap in 2019 as she prepared to travel to Oak Flat to support Nosie and Apache Stronghold.

“Would we blow a crater into Mt. Sinai? Would we dare to tear open the earth in Bethlehem, or poison the waters in Galilee? Millions across the world were horrified when Notre Dame burned and yet here we are, days before setting the match on one of the most sacred sites in North America for Apache and for hundreds of tribes,” she said in a statement.

“This sinful sale of holy land is a threat to all of our constitutional rights to practice our religion.”

Debra Krol covers issues related to Indigenous communities in Arizona and the intermountain West. Reach the reporter at [email protected] or at 602-444-8490. Follow her on Twitter @debkrol.

Coverage of Indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and commerce is supported by the Catena Foundation and the Water Funder Initiative.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.