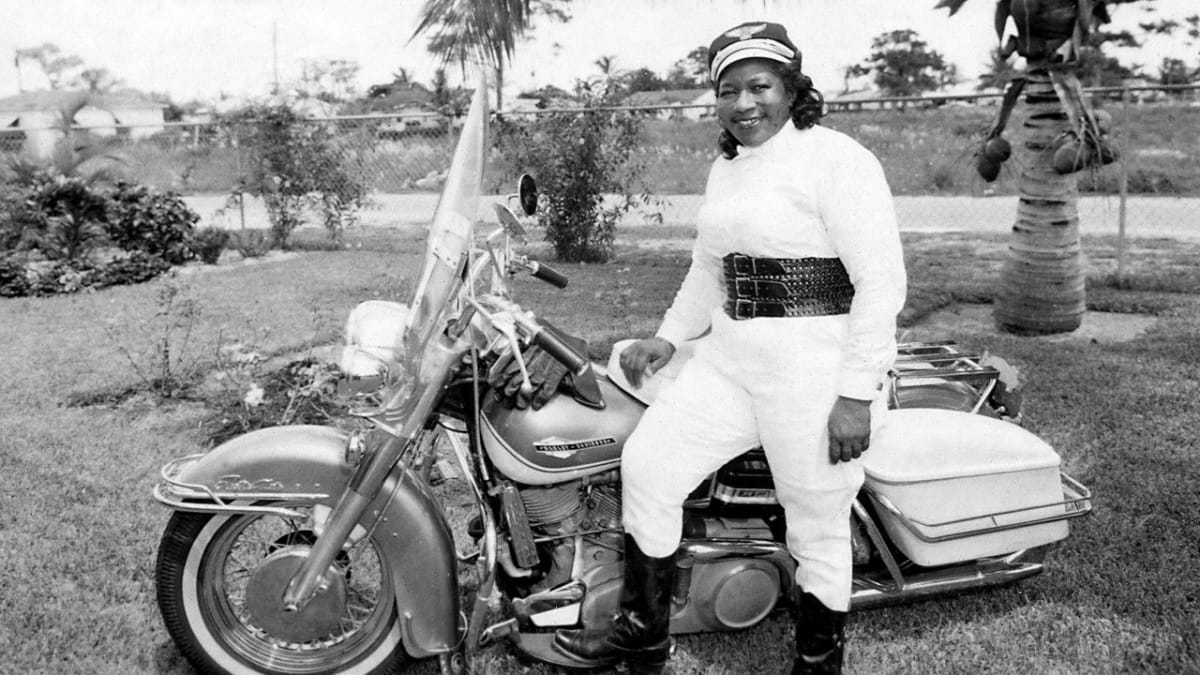

Bessie Stringfield was the motorcycle queen of the 1930s

During the Jim Crow era, a time when Black Americans were segregated based on the color of their skin, a young Bessie Stringfield set out to explore the open road with her motorcycle. Little did she know that her motorcycle ride across the United States would break barriers not only for women but African-American motorcycle riders as well.

Bessie Stringfield, the motorcycle queen of the 1930s, was a passionate bike enthusiast who enjoyed the open road and the freedom it provided. Bessie had a unique story.

According to The New York Times, Bessie Beatrice White was born in March 1911 to James Richard White and Maggie Cherry of North Carolina. But Bessie wanted to create a new origin story for herself, so she transformed herself into Betsy Leonora Ellis, an orphan immigrant from Jamaica.

Reported in multiple news outlets, the story that Bessie created was of a girl born on February 9, 1911, to Maria Ellis and James Ferguson in Kingston, Jamaica. Seeking a new home in the States, her parents migrated with young Bessie to Boston, Massachusetts. But their American dream was cut short. Shortly after arriving in Boston, both Bessie’s parents fell ill to smallpox and later died, leaving 5-year-old Bessie an orphan. A wealthy Irish woman adopted young Bessie. During her teen years, Bessie received a gift from her adopted mother, a 1928 Indian Scout motorcycle. Although this story of her upbringing was fabricated, it does not blunt the accomplishments that led her to the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

Bessie began mastering the craft of motorcycle riding in her teens. Before riding across the country, she built up her confidence by first charting routes on a map. In early 1930, Bessie saddled up and headed on her first transcontinental trek, during the Jim Crow era. During the 1930s and early 1940s, she would complete eight cross-country treks.

As she traveled on her Indian Scout, Bessie would earn money performing motorcycle stunts at carnivals along her routes. If there was nowhere for her to get a good night’s sleep, she slept right on top of her motorcycle at a gas station. Bessie faced life-threatening racial prejudice during her time on the road — she was knocked down by a truck while traveling in the South — but that never stopped her from enjoying the freedom her motorcycle provided.

Stringfield stopped her long cross-country treks in the 1950s, but her adventures continued on. Bessie entered an all-male motorcycle race and won first place, but she was denied the prize when she revealed she was a woman by removing her helmet.

Her determination, passion and courage broke barriers for women and African-American motorcycle enthusiasts. Thanks to her will and adventure-seeking personality, as well as numerous motorcycling achievements, Bessie Stringfield was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2002. Sadly, it was nearly a decade after she died in 1993. She is also featured at the Motorcycle Heritage Museum in Pickerington, Ohio.

To read more about Bessie Stringfield and her many adventures, click the links below: